The Tender Trap Part 1: Procuring

By

Ian Harris and Professor Michael Mainelli

Published by Charity Finance, Plaza Publishing Limited, pages 42-43.

Charities increasingly find themselves required to put in competitive tenders in order to win public sector contracts. Similarly, charities increasingly require their suppliers to go through structured tendering processes. But often those structured tendering processes are inappropriate for the procurement situation. In this first of two articles for Charity Finance, Ian Harris and Michael Mainelli of The Z/Yen Group examine “The Tender Trap” from the buying perspective for charities. [See Part 2]

You’re Thinking Nothing’s Wrong

Charity people often complain to us about the unreasonable and inappropriate demands of the public procurement processes required of them to win public sector contracts. Indeed, Part two of this article (to appear in the next issue of Charity Finance) will discuss “The Tender Trap” from the point of view of charities as the seller. Yet, often, those same charities are adopting “public procurement”-style processes when purchasing.

While we endorse the need for charities procurement to be transparent and demonstrably above board, we believe that structured tendering processes are often used inappropriately by charities. While half-buried behind some extensive procurement process checklist, the buyer is often also hidden from any chance of thinking clearly about the choices available. And structured tendering tends to drive the innovation out of selling. If you receive a detailed specification of the products and/or services required, it takes a brave seller to tell the procurement people that they might have specified the job incorrectly. Far easier (and far more lucrative) to simply sell the things that have been have asked for.

You String Along, Boy, Then Snap!

Here’s a real-world example. A friend of ours sells design consultancy services, often to the charity sector. To protect his identity we’ll simply refer to this as “Nigel’s Story”. Nigel’s company was invited to tender by an environmental non-governmental organisation (ENGO).

As Nigel put it “they were asking for an enormous amount of information and this was just the pre-qualification questionnaire (65 pages long); I dread to think what the actual tender process would be like. A lot of the questions were obscure and could be interpreted in all manner of ways. It became clear at the open meeting that they didn’t really understand what they were asking for, nor did they understand the distinction between the myriad of ‘lots’ against which we were expected to respond.”

Nigel goes on, “the key to me is that this sort of process demonstrates that the buying organisation does not understand the market it is buying in. In the interests of standardised procurement, the buyers paid no attention to the credibility and track record of the companies involved. I suspect that many good companies were, like us, put off by these processes and simply declined to get involved. This leaves bodies like this ENGO using second rate outfits”.

You’re acting kind of smart

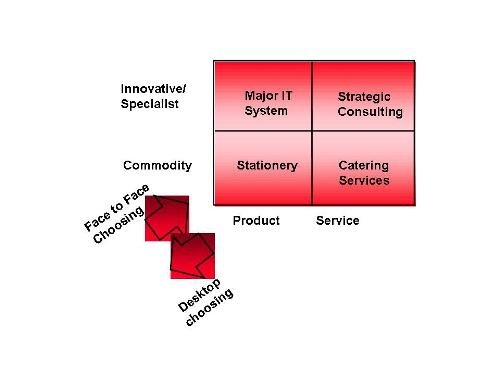

Of course, charities procure a huge variety of different products and services; different procurement styles suit different types of purchase. The diagram below illustrates procurement types with examples of each, using our old friend the two-by-two matrix.

Diagram One: Procurement Types and Examples

The bottom left-hand corner of the matrix covers commoditised products. A good example is stationery. This type of purchase lends itself to back-office or desktop choosing, e.g. by catalogue. The top right-hand corner of the matrix relates to more innovative, specialised and service-based offerings. An example dear to our hearts is strategic consulting. This type of purchase usually requires face-to-face choosing; good choices tend to need hands-on, investigative and/or iterative approaches. The top left-hand corner of the matrix relates to those innovative and/or specialised purchases that are more product-oriented. A major IT system is a good example. In this example, a tender-based approach, combined with an element of hands-on selection, is often an appropriate way to make a good choice. The bottom right-hand corner relates to the more commoditised service offerings. Catering is a good example. Here, an element of catalogue style choosing is appropriate, although this should be combined with some hands-on evaluation of service providers.

Until your heart just goes wap!

You quite often come across “tendering processes” for commoditised purchases, where the buyer is going to a great deal of trouble to try and run a proper process but cartels of sellers “fix” the process by providing inflated quotes for each other on a reciprocal basis. This bad practice is very common in vehicle repairs and property decoration contracts. To find best price, the buyer really wants to use negotiation, but sometimes finds itself hide-bound by its own procurement process until too late a stage to be able to negotiate best price. At the other end of the spectrum, you often come across formal tendering processes for innovative and/or strategic services, even though it is nigh-on impossible to specify the services (often you don’t even know what you want to buy). The main problem in this instance is that the very process of specification and tendering is likely to drive away most if not all the innovation you seek, by putting off the more innovative suppliers and/or by encouraging suppliers to narrow their vision in order to comply with the specification and the tendering process. Nigel’s Story (above) is a typical example of this problem. Further, those charities that model their entire procurement processes on public sector procurement rules, tend to know instinctively that the processes don’t work in all cases and sidestep their own rules when it suits them. I haven’t had the heart to tell Nigel that the very ENGO that caused him all that grief, recently procured some services from Z/Yen (albeit a small assignment) with no more than a simple letter proposal; no competition and certainly no onerous prequalification questionnaire.

You hurry to a spot that’s just a dot on the map

Another way of looking at the above conundrums is to think about procurement as a mixture of both buying and shopping. Formal procurement processes tend to be essentially about “buying”, but for many types of purchase there should be a significant element of “shopping” involved. We could harp on stories that suggest that “buying is from Mars and shopping is from Venus” but perhaps there are too many stereotype pitfalls in that line of discussion. However, the following table takes a (mostly) considered view on the characteristics of buying and shopping.

Buyers Shopping Preconditioned See possibilities Often pre-decided Often exploratory Compare prices Compare features One-off process Learning process Quick process Iterative process Hunt down purchase Tease out purchase From Mars? From Venus?

Looking back at the matrix in Diagram One, straightforward buying is quite possibly all you need in the bottom left-hand corner, “commoditised product” section. But almost anything else that you procure (most of the purchases and probably the most important purchases) benefit from elements of shopping as well as buying.

Part of the Tender Trap

To summarise this first part of the Tender Trap, here is a mini procurement manifesto for the buying side of the charity:

- Charities should aim to be professional and transparent in their procurement. But “more tendering” does not equate with “more professional” and/or “more transparent”;

- Charities should set criteria for their procurement, but in most cases they should “window shop up front” so that valid criteria can evolve and emerge;

- When charities seek innovation, they should avoid large and formal tendering processes. There are other ways of ensuring that the procurement is fair and transparent (e.g. meeting several suppliers up front but only inviting two or three to make formal proposals);

- Ensure that your charity learns from procurement processes by formalising the learning part; strangely that is one part of the process that tends to remain informal and often is not done at all;

- Don’t choose suppliers merely on the quality of their presentations; you are very rarely seeking to buy presentation skills, yet very often charities choose supplier on the quality of the presentation rather than the content.

In Part two of this article, we’ll discuss the Tender Trap from the point of view of charities selling their services.

Ian Harris and Professor Michael Mainelli are Directors of Z/Yen Group Limited, a risk/reward management practice, dedicated to helping organisations prosper by making better choices (www.zyen.com). Z/Yen clients include blue chip companies in banking, insurance, distribution and service companies as well as many charities and other non-governmental organisations.

[An edited version of this article first appeared as “The Tender Trap”, Charity Finance, Plaza Publishing Limited (December 2007) pages 42-43.]