The Consequences Of Choice

By

Professor Michael Mainelli

Published by European Business Forum, Issue 13, Community of European Management Schools and PricewaterhouseCoopers, pages 23-26.

Risk Society

In today’s world, what prevents managers from managing? Actually, quite a lot. Managers make decisions for organisations. When managers’ freedom to choose is curtailed, decisions can be sub-optimal or wrong. Yet, untrammeled power to choose leads to the frontiers of despotism. Society expects more and more from organisations, but the means used to impose societal expectations are crude, either feeble recommendations or daunting legal and regulatory mechanisms.

The burden of regulation and quasi-regulation is increasing - the 1992 Cadbury Report, 1995 Greenbury Report, 1998 Hampel Report, 1999 Turnbull Report and 2003 Higgs report; German KonTraG corporate governance reforms; Sarbanes-Oxley; and the OECD Principles of Corporate Governance. Robertson [2002] points to both the enormous number of Corporate Social Responsibility issues and the lack of appropriate management response. Henderson [2001] argues forcefully that the burden of Corporate Social Responsibility on commercial organisations is harming organisations and society.

While the increasing burden of social responsibility may be a sign of an affluent society moving towards a risk society, i.e., one which has moved from relations based on production to relations based on risk [Beck, 1992], nevertheless an organization “has a job to do”. At the same time as society imposes “mandatory initiatives”, there are numerous organizational initiatives. CEOs, COOs, board directors, or governing council members manage by memo … “all staff must at all times…”.

They Pretend to Let Us Choose, We Pretend to Manage

Can managers comply with all mandatory initiatives? Probably not. Each mandatory initiative reveals the weight of its presence in bureaucratic procedures. One military organization insists on blowing a whistle before test missile firing in order to clear grouse. The “grouse whistle” was mandated after a Scottish incident, but decades later is wasting time in many theatres where grouse are scarce to the point of non-existence. While this example verges on cute, the cumulative effect of procedures on this organization is sclerotic. One public sector senior manager brought a large mannequin covered in 47 balloons before colleagues on an awayday. In order to punctuate his talk, he burst a balloon while reading out 47 “mandatory initiatives” and their time requirements. The culmination of his talk was that complying with mandatory initiatives left his team with no time to work.

It resembles a “conspiracy” between senior executives and the rest of the organization - “we’ve got to bury you in procedures and you’ve got to violate them. Just don’t get caught, and if you do, we’ll all blame the procedures.” The absurdity of procedural overload is never clearer than in a corporate accident investigation report. Every accident investigation report seems to state “certain procedures were not implemented …”. Sometimes, though rarely, the report may state that “even had all procedures been followed … the accident may not have been prevented.” Naturally, every accident investigation report goes on to recommend more bureaucratic procedures. Senior executives claim to delegate, but impose mandatory initiatives and don’t want to hear the bad news that procedures are routinely violated. No wonder many large organizations are dysfunctional.

The above may seem like a whinge about corporate social responsibility and the inevitable laws, regulations and procedures that seem to result. Far from it. The post-modern risk societal problem is how to hold post-modern organizations to social goals while still permitting them to add value. The remainder of this paper examines two increasingly common approaches to the problem:

- a focus on risk and using activity-based costing variances;

- establishing enterprise risk/reward units using a single “currency”.

Disciples of Risk And Activity-Based Costing Variance

The popularity of risk management is due to the high impact some simple ideas and tools provide, because a risk perspective allows everything - costs, variances, flexibility, complex contracts, quality measures – to be defined as a financial impact. Risk managers are found in diverse environments and roles, e.g. health & safety, insurance, project management, credit risk, business continuity or quality.

“Risk is the probability of an adverse occurrence multiplied by the impact of that adverse occurrence. Risk literature discriminates among “risk” as a chance or probability, “hazard” as a dangerous object or condition, “threat” as an indication of an object or condition that could influence the level of risk. For instance, risk of theft might have a weighted probability of €30,000; hazard, an unlocked door; threat, organised crime.”

Risk is intimately related to quality – are activities “fit for purpose”? One overriding principle in leading organisations is the importance of measuring variance in costs and quality as a prime metric for risk. High-risk processes correlate with high cost variances. In turn, high cost variances correlate with lower quality outputs. Quality-obsessive industries constantly measure cost variances to detect quality problems. Activity-based costing systems are essential. Companies attempt to include the full process cost, not just direct costs such as raw materials but also rework, wastage, scrap, disputes, returns, environmental fines, etc.

A good first step in risk management is to develop “full” per-transaction costings and examine variances by product line. Despite the ubiquity of cost variances in manufacturing plants, it is rare to find this sensible measurement approach in the boardroom. But can cost variances capture social costs? Can the outcomes of good social responsibility choices reward managers, and bad choices cost managers?

Choose, In Your Currency

If post-modern organisations are going to free managers to manage, organizations must support managers in making choices. Experience shows that genuine change requires new values and new rewards, i.e., the organization must align terms and conditions [Mainelli, 1992]. Examine two managers in the same organization at their annual appraisal:

Cruella E-ville: “Sure I’ve cut a few corners around here, who wouldn’t, but we’ve managed to implement one heck of an e-commerce system in just 12 months. A few early customers probably won’t return, but month on month our turnover is rising. I realise the paperwork’s a bit behind, the press has been a bit harsh and I don’t really want to get into those two lawsuits for sexual harassment; after all you need a bit of spirit when you’re driving a team hard with such high staff turnover. Despite the problems, I’ve made a heck of a lot of profit and am looking forward to a cracking bonus.”

Goodie Twoshoes: “Well I realise you’re looking forward to our e-commerce system rolling out anytime now, as it is six months behind schedule, but we should really look at the bigger picture. All staff are highly motivated, as evidenced by the human resources department; training schedules are fully met; staff have been on appropriate sensitivity courses; and the entire division has achieved several kitemarks for excellent management. I’m particularly pleased at our compliance with recent corporate work/lifestyle balance initiatives. Despite our lack of profit, I’m looking forward to an outstanding bonus for all this hard work.”

Cruella E-ville has made profit her primary goal. Goodie Twoshoes has made compliance with mandatory initiatives her primary goal. Neither manager can be criticised. They have not been given the tools to choose between conflicting goals or a single variable to optimise. They have not been given an “algorithm” that would allow them to convert sub-optimal performance on profit into socially responsible goals, or vice versa. In effect, Cruella E-Ville and Goodie Twoshoes are being evaluated in a variety of “currencies”, e.g. the profit currency, the compliance currency, the staff satisfaction currency, etc.

A variety of business thinkers promote “leadership” as a way of cutting through these complex trade-offs. However, the leader can’t be everywhere. Not all decisions are suited to simple solutions. Some leadership styles may work with the front-facing parts of the organisation, e.g. projects or sales, but not with others, e.g. finance or logistics. Sometimes there aren’t leaders. Another set of business thinkers promotes “culture” as way of calculating trade-offs. Culture is “the way we do things around here.” What’s needed is a system of making choices that combines complex parameters into as few variables as possible. Perhaps culture could be more accurately defined as “the way we decide to do things around here”.

Financial decision theory has attempted to put finance forward, with some success, as a meta-decision framework for organizations, encompassing alternative financing and debt/equity trade-offs (Capital Asset Pricing Model), shareholder value added (hurdle rates, risk-adjusted return on capital), time cost of money (Net Present Value) and volatility (risk/reward options). Finance provides a single “currency” for corporate decisions. Can this financial model be reconciled with social responsibility decisions?

Consensus Choice

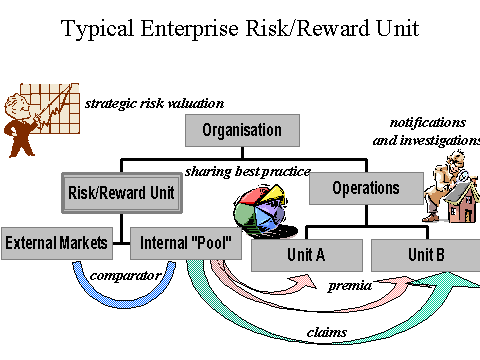

Evidence of an emerging consenus comes from a benchmark of risk management by Moffatt Associates in 1997. Fluor, Gillette, British Aerospace, Schlumberger, Microsoft and Northrop Grumman attempted to compare principles and procedures, briefing and communication, risk transfer and financing. Some organisations were risk-exposure driven, some functionally risk-focused, some site-driven, in businesses changing at different rates, yet certain processes were common. The common processes among these and other industrial firms are increasingly managed by one entity, an enterprise risk/reward unit:

“Enterprise risk/reward management applies organisational knowledge to make better decisions about risk and reward through market pricing and capital charges.”

The essence of enterprise risk/reward management is that organizations change culture by changing choices using an internal risk market that shares knowledge and alters capital charges, through:

- strategic risk valuation: encouraging the organisation to look at all its risks, not just financial ones, and forcing the board to see total risk and initiative costs;

- internal “premia” and “claims” management: showing line managers the financial implications and results of risks while also reducing external insurance costs, often by 25%;

- notifications and investigations: actively reporting and investigating near misses and incidents in order to learn;

- sharing best practice: using information on risks gained from notifications and investigations and comparisons which permit line managers to learn from each other;

- external comparators: providing comparative information on risk management from links with external markets, e.g. reinsurers, bond rates, benchmarking databases;

- fewer crises: overall corporate volatility and exposure should be reduced.

Case Study - No Cost, No Pain, No Gain

In one aerospace organisation, each project, site and legal entity must obtain a notional insurance premium from the enterprise risk/reward unit located within the finance department. The premium covers the manager of the entity from a list of specific risks, permitting him or her to achieve P&L objectives within a framework of calculated risk. In return the manager must comply with typical insurance policy requirements, submit to rigorous early incident reporting and share risk data. Most of the risks are ‘hard’ (balance sheet) risks, replacing common external insurances such as fire, loss of personal computers or professional indemnity with a premium deducted from the manager’s cost centre. In effect, the enterprise risk/reward unit functions as an “internal mutual insurer” for the various divisions of the organisation.

Every year, the organisation will have some fires, lose some PCs and have some lawsuits. However, insurance is value-for-money at a managerial level. Why should my otherwise excellent departmental results be ruined by the loss of 20 PCs when I can insure against the loss? The ability to show managers the financial consequences of risk allows managers to make more informed decisions and see bottom-line results as premia rise or fall. Sharing information among managers about premia, near misses and claims builds knowledge, contrast this with external insurances where both parties suppress data in order to preserve bargaining power gained through asymmetric information.

Stretching Measures

The following diagram illustrates scope and activities of an enterprise risk/reward unit:

‘Soft’ risks can also be managed. For a manager who engages in politically risky projects, a political risk premium may be significant enough to negotiate with the risk/reward unit on what will reduce the premium, e.g. restricting the types of projects accepted or avoiding certain overseas locations. Premia can also stimulate appropriate investment beyond the financial year. When one manager queried a comparatively high manufacturing plant premium, he was told that the principal problem was the lack of a retaining wall and a secure storage facility for hazardous gases. He was able to use agreed premium reductions to show a two-year payback for a capital improvement that had been ignored in previous annual expenditure rounds.

Industry tends to give control of enterprise risk/reward units to finance [Mainelli, 1999]. Some firms have experimented with estimating the amount of capital tied up in risk, used risk/reward options to value risk-reduction projects, or even set up competing enterprise risk/reward units within the same organisation. An enterprise risk/reward unit’s performance can be measured through benchmarking, customer satisfaction and financial returns.

Choosing Choice

Choice is a 21st century theme. One person’s freedom to choose imposes costs on another. This is as true within organizations as within society. Society cannot continue to ignore the costs that mandatory initiatives impose. At the same time, organizations cannot ignore the fact that society’s demands require more sophisticated, yet paradoxically more simple, management systems united in a single “currency”. If managers operate within a risk/reward framework, then they can make informed, balanced choices. Enterprise risk/reward management devolves decisions back to managers who learn as the consequences of their decisions come back to them in changes to their rewards.

Strategy pushes the organisation forward, while an enterprise risk/reward unit ensures it doesn’t unwittingly expose itself to risks which haven’t been properly evaluated. To use a metaphor, strategy pushes you along a chosen path; risk/reward stops things pushing you off. Enterprise risk/reward units can free organizations, while ensuring they meet appropriate social responsibilities.

References

Stephanie Robertson, Dilemmas in Competitiveness, Community and Citizenship, The London School of Economics and Political Science, August 2002.

David Henderson, Misguided Virtue: False Notions of Corporate Social Responsibility, Hobart paper 142, Institute of Economic Affairs, London, 2001.

Ulrich Beck, Risk Society: Towards A New Modernity, (Mark Ritter, translator) Sage Publications, 1992.

Michael Mainelli, "Vision into Action: A Study of Corporate Culture", Journal of Strategic Change, Vol 1, John Wiley & Sons, pages 189-201, 1992.

Michael Mainelli, “Wither the FD? Hello Risk/Reward Director!”, Handbook of Risk Management, Issue 30, pages 5-7, Kluwer Publishing (12 July 1999).

[An edited version of this article appeared as "The Consequences of Choice" , European Business Forum, Issue 13, Community of European Management Schools and PricewaterhouseCoopers (Spring 2003) pages 23-26.]