International Student University Fee Guarantee Scheme

International Student University Fee Guarantee Scheme - An Outline Proposal, 2021

Summary

An International Student University Fee Guarantee Scheme (ISUFGS) would provide an insurance policy for international students that their fees for UK university attendance are secure in the event of certain risks materialising, specifically bankruptcy of their chosen institution, but potentially wider risks. Such a scheme should help UK universities be more competitive in international markets.

London Higher would like to explore developing a policy proposal for an ISUFGS to share with the Department for Education. This outline proposal describes why such a scheme is needed, the benefits, how it might work, and some immediate next steps.

International Markets & UK Universities

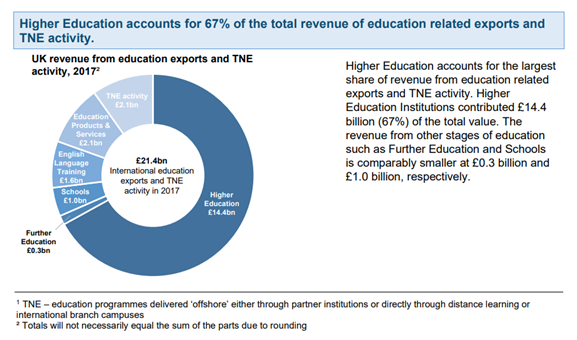

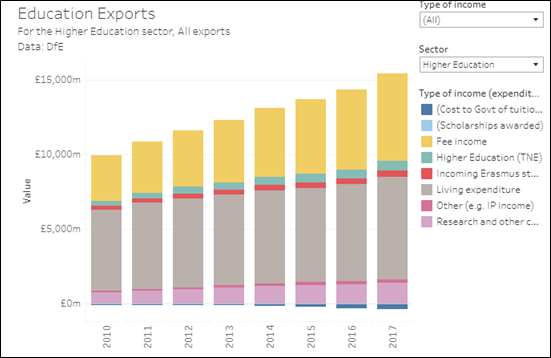

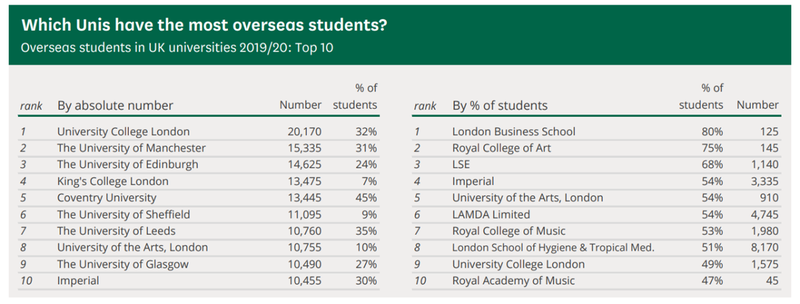

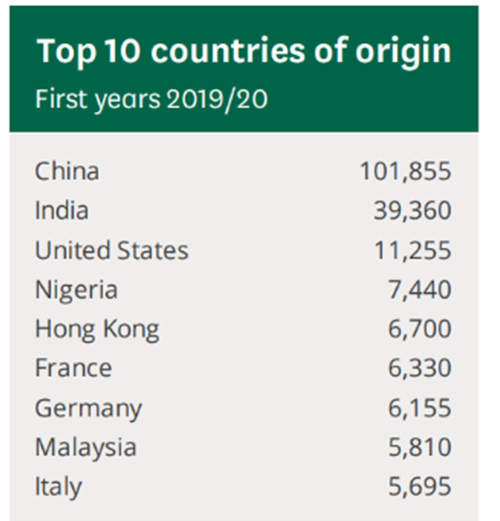

UK Universities are an important ‘export’ market for the UK, generating over £10 billion per annum in fees for international students, as well as considerable spill-over expenditure perhaps three times as high. In 2019/20 there were 538,600 overseas students studying at UK universities; 22% of the total student population. 143,000 were from the EU and 395,6000 from other international locations.

For 2014/15 Universities UK estimated that international students contributed around £25.8 billion in gross output to the UK economy, leaving aside ‘soft power’ benefits, though this exceeds official statistics. Starting with the Department for Education numbers, where it’s important to realise that the numbers include estimates, e.g. living expenditure in the UK, not just fees. Living expenditure income alone is more than fees:

“We have no idea how much education related exports are worth to the UK”, David Kernohan, Wonkhe, 6 December 2019

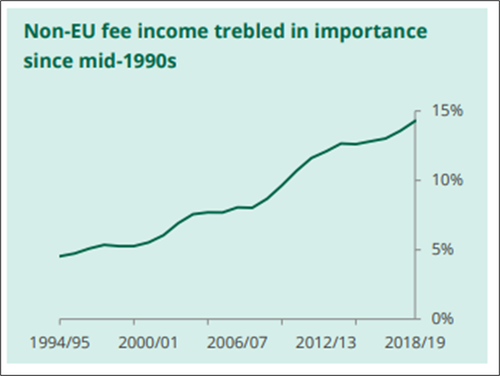

Nevertheless, higher education and university ‘exports’ are increasing and increasingly important as a sector. On 6 February 2021 the Government launched an updated International Education Strategy – which reaffirmed its aims to recruit 600,000 international higher education students annually and increase education exports to £35 billion a year by 2030. The Government has introduced a two-year Graduate Route post study work visa and a three year visa for PhD graduates.

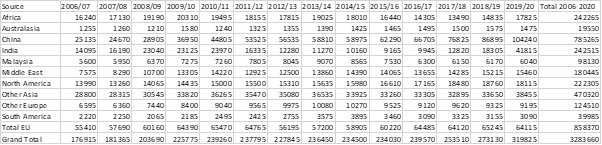

Performance over the past four years has shown marked improvement in raw numbers from a decade ago. New overseas entrants to UK universities fell from almost 240,000 in 2010/11 to just over 230,000 in 2015/16.

Over the past four years overseas entrants grew attaining a high of 307,800 in 2019/20. In 2017 the US took 26% of all higher education students who were studying overseas at universities in the OECD. The UK was in second place with 12%. But market share has been slipping and other English-speaking countries such as Australia, New Zealand and Canada have seen significant absolute and percentage increases in overseas students.

Going forward, there will be no distinction of EU and non-EU students; they will all be ‘international’ or ‘overseas’ students. There has been a general drop in entrants from the major EU countries since 2011/12; Ireland down by 43%, Cyprus 36%, Germany 29%, Greece 26% and France 18%. Italy and Spain were the exception with numbers up by almost half.

The importance of international students to the economy is significant to the UK economy. The importance of a stable international student market is crucial to most UK universities.

International Competition

An ISUFGS is a form of mutual insurance designed to cover the costs of supplying basic protection and support to international students whose chosen provider has failed. Typically the schemes cover compensation of fees or transfer costs into a new provider.

Such a collective insurance scheme mimics ABTA’s (Association of British Travel Agents) Common Fund (1965) that repatriates stranded holidaymakers, refunds deposits, or provides alternative holidays, as well as the Air Travel Organisers’ Licensing financial protection scheme for holidaymakers’ air travel.

Australia has had the premier ISFUGS since 2000, the Education Services for Overseas Students (ESOS) Assurance Fund. ESOS is a mandatory scheme with 1,200 higher education providers paying a risk-based premium into the fund. It requires providers to pay into an assurance fund and engage with a ‘tuition protection service’ that ensures students are provided with suitable alternative courses, or have their course monies refunded, if the provider is unable to provide the course(s) that the student has paid for.

Proposal

The ISUFG policy proposal at its simplest is:

To provide the opportunity for international students to have insurance cover for reimbursement of fees paid/payable in the event of ‘failure’ of their UK university to deliver a course.

The principal benefits of an ISUFGS are:

- protection of the shared UK university brand in international markets;

- better and more stable brand positioning;

- a more confident international student experience;

- in the event of an institutional failure, a smoother transition and the retention of more of the international business already contracted.

Such insurance cover could be:

- provided by the government as a direct guarantee;

- purchased by the student as part of their fees;

- purchased by the student as an optional extra;

- purchased by the university on behalf of the student.

Is There A Need For An ISUFGS In The UK?

Baldly, if a university in the UK were to go bust, what would happen to their students and the UK’s reputation as the gold standard of universities? At the moment their students would be left without recourse to compensation or a defined means to complete their courses elsewhere.

There are less catastrophic failures to deliver, for example course cancellations or department closures. An ISUFGS would give some universities more flexibility to explore curriculum development.

There are ‘failure’ precedents in the UK that have affected the UK brand. Over the summer of 2011 a number of unregulated private providers of higher education (‘bogus colleges’) closed because they could not, or would not, comply with new UKBA regulations concerning student tracking. In most cases the students at these colleges were left uncompensated. Pressure groups picked up on the story with headlines such as “UK: TASMAC debacle prompts call for guarantees” in University World News (21 October 2011), “International Students 'Cheated' Out Of Thousands By Private UK Colleges”, Huffington Post (2 June 2012).

A related incident at the same time was that the UK government’s crackdown on visas led to Indian students in particular being denied visas despite more than half of them having valid UK university places. When they tried to reclaim their funds, UK universities were extremely uncooperative, claiming they failed to turn up. The recent enormous rise in Indian student numbers shown below is probably more due to memories of that poor behaviour by many UK universities fading, and not due to better marketing.

As can be seen below, overseas perceptions matter. After the difficulties in a market that should be significant for historic and cultural reasons, Indian student numbers plummeted from 23,970 in 2010/11 to 16,335 in 2011/12 because of the reputation of UK universities over the visa problems. It took till 2019/20 for numbers to go above the previous 2010/11 mark despite an otherwise rising market.

In the past the expectation has been that failing public institutions would be saved from closure, either through restructuring or other support. However the UK Government has sent clear signals that this expectation is unwarranted, starting with the 2011 White Paper - “…the Government does not guarantee to underwrite universities and colleges. They are independent, and it is not Government’s role to protect an unviable institution…” (BIS, 2011: 6.9b Pp. 67).

One might expect that many institutions will view a failure down the line as hardly relevant to them. They will see themselves as distinct from the failure on many different levels, from their location, programme offering, financial position, mission, student experience, etc. A messy failure, with students left unsupported, especially where other countries are able point to ISUFGS arrangements of their own, would damage the UK’s brand and give the perception that UK higher education is complacent.

Who Should Take Responsibility For ISUFGS?

Such a scheme can be national and mandatory, or voluntary and cover only willing participants. Such a scheme does not ‘need’ government support, though a group of universities setting up such a scheme does make an indirect statement about universities not in the scheme.

One reason for developing a policy proposal to share with government is that government support could change an ISUFGS structure markedly for the better. Strong government support could render such a proposal redundant, i.e. the government states that it will guarantee international student fees across the UK in the event of default. If the government were to do that, then this policy proposal is less essential and UK universities gain strength in international markets at no cost. A more limited ISUFGS might look to cover closure of a course or department.

Middling government support could range from providing indirect certification of a UK scheme or UK schemes in international markets, making participation in a scheme mandatory, perhaps also adding ‘pandemic’ or other risk funding support.

No government support, but benign acquiescence, might mean a narrower scheme of voluntary participants in an existing entity, such as London Higher only.

Potential Restriction Or Extension

Membership – an ISUFGS could be restricted to just London Higher members, at least at first, or to just English universities. Some narrowing of membership might make getting started easier. There is the potential to have a few competing schemes, rather than a national one.

Sectors – an ISUFGS could be extended to other educational sectors in the UK that compete in the international market, such as private secondary schools or further education colleges. Equally, it could be extended to UK students if that seemed appropriate. Or a working ISUFGS could be an inspiration to similar but separate schemes for such sectors.

Risks – the international student faces a number of other risks that could be included in a widening of the coverage:

- visas – inability to obtain a visa could be covered;

- travel to the UK – due to events such as a pandemic or loss of air travel for some extended period, are potential extensions to the cover;

- political risk – international boycotts or travel bans on some countries are potentially coverable;

- health – if ill health led to non-attendance, this could be an extension to cover;

- currency risk – there is a possibility to extend to covering currency fluctuations over a multi-year degree.

Policy Proposal Scope

The policy proposal would probably not recommend the potential extensions above. The policy proposal would suggest a feasibility study that would include:

- joint exploration with government of the idea of an ISUFGS;

- defining the extent of cover, i.e. what is ‘failure’?

- deeper examination of the Australian ESOS and understanding its development of the past twenty years, as well as a survey of other ISUFGSs;

- more supporting documentation with financial and risk assessments;

- a survey of UK universities on their interest in the policy;

- initial discussions about managing and funding such a scheme with mutual managers, insurers, and reinsurers, such as Thomas Miller & Co, Charles Taylor & Co, UMAL (the universities’ mutual);

- considering how to fund the UK ISUFGS;

- setting out a limited range of options for government to select from.

Next Steps

‘Timing is everything’ with policy proposals. The Australian model was pointed out to government a decade ago, and now has two decades of success. However, the current government’s ‘Global Britain’ theme, the need for stronger trade & exports, and more liberal thinking about government’s role and finances might indicate that speed is of the essence in getting such a proposal before government soon.

For London Higher, the next two steps are:

1 – decision to proceed, defer, or reject policy proposal development.

2 – develop a policy proposal for discussion with the Department of Education.

Further Reading

Research Briefing, “International and EU students in higher education in the UK FAQs”, House of Commons Library, 15 February 2021.

Australian Government Education Services for Overseas Students Tuition Protection Service:

For education providers - https://internationaleducation.gov.au/regulatory-information/Education-Services-for-Overseas-Students-ESOS-Legislative-Framework/ESOS-Review/Documents/TPSProviderBrochure.pdf

ESOS Legislative Framework -

FAQs - https://tps.gov.au/StaticContent/Get/FaqsForStudents

How the Australian government explains ESOS to students - https://wahroonga.adventist.edu.au/files/1315/9894/8960/Easy_Guide_to_ESOS.pdf

How providers explain ESOS to students (Kaplan Business School) - https://www.kbs.edu.au/documents/statement-tuition-assurance-and-tuition-protection-service-policy