The Three Rs

By

Ian Harris and Brendan May

Published by Charity Finance, Plaza Publishing Limited, pages 44-46.

Setting the scene

The Marine Stewardship Council(MSC) is an independent, global, non-profit organisation based in London. In a bid to reverse the continued decline in the world's fisheries, the MSC is seeking to harness consumer purchasing power to generate change and promote environmentally responsible stewardship of the world's most important renewable food source. The MSC has developed an environmental standard for sustainable and well-managed fisheries. Recent headlines on the crisis in fish stocks around the world demonstrate just how pressing an environmental issue this is. The MSC began its work in 1999. In its short life, the MSC has already engaged with 40 major world fisheries, fifteen of which are either certified or in the final stages of certification. The MSC is rapidly becoming well known in political, commercial and end-consumer circles.

Z/Yen Limited (Z/Yen) is a risk/reward management practice. Risk/reward management is the application of risk analysis and return incentives to strategic, systems, human and organisational problems in order to improve performance. Z/Yen’s clients include blue chip companies in banking, technology and professional services as well as charities. Z/Yen has been working with the MSC over the last two years to help the MSC develop and thrive.

The Three R’s

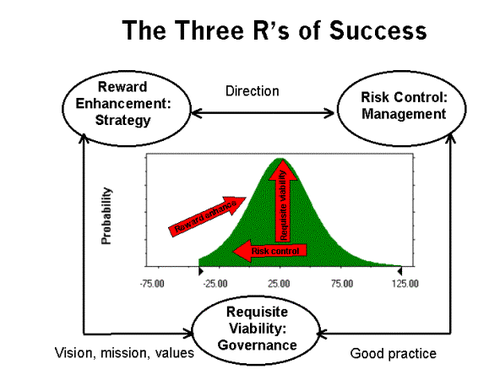

There are three main aspects to organisational improvement and success: risk control, reward enhancement and requisite viability. The following diagram illustrates these aspects and the relationships between them; the table below summarises them.

| Outcomes Sought | Activity required | Probabilistic evidence |

|---|---|---|

| risk control | the intelligent management of risk | elimination, mitigation or transfer of major downside risks |

| reward enhancement | strategic planning to maximize the achievement of objectives | shift enabling increased performance at given input levels |

| requisite viability | stable yet flexible governance | increased decision-making flexibility and/or reduced outcome volatility |

The MSC’s outstanding work on all three of these areas earned them several commendations and awards in 2002, including a Best Practice Award at the Charity Times awards and a commendation in the environmental category at the Charity Finance Awards.

Risk control

In an age of increasing accountability expectations, which are as important for the not-for-profit sector as any other, the MSC devised a risk management framework and risk manuals towards the end of 2001. Z/Yen facilitated and documented the work. The resulting framework was grounded in corporate good practice (Cadbury, Greenbury, Hampel & Turnbull) and viable systems theory.

The MSC’s risk management policy is set out below.

“It is the Marine Stewardship Council’s policy to have a Risk Management Framework which:

¨ attempts to identify, assess and manage all MSC risks;

¨ supports the strategic plan;

¨ assigns clear responsibilities for risk management;

¨ monitors and tracks individual, departmental and MSC progress on managing risks.”

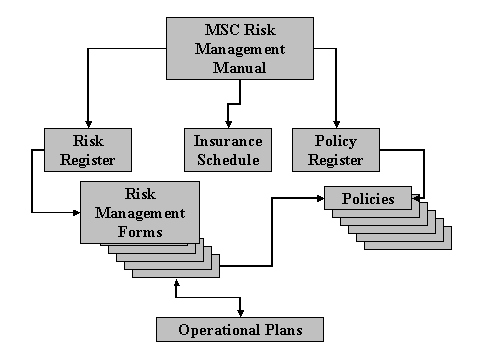

The framework sets out the responsibilities and management system for MSC risk management. The framework contains the following key documents:

At the outset, the MSC Executive were worried that the risk management framework would be an additional layer of bureaucracy with little or no tangible benefit to the MSC. In fact, the exercise has benefited the MSC, enabling the Executive to understand and manage its risks better, thus enabling it to achieve more rewards by assuming additional risks. Those risks might be external (for example lack of support in key sectors, opposition from government or funding constraints) or internal (such as problems with the science behind the MSC programme). If charities do not at least identify risks, they cannot be managed, and potential rewards can often be missed.

Reward enhancement

Prior to devising the Risk Management Framework, the MSC undertook a strategic planning exercise in early 2001. The MSC held a series of management workshops with staff over a period of three months, plus follow-up consultation with stakeholders. A key output of that exercise was the MSC’s statement of vision, mission and values. For example, the MSC’s mission is “To safeguard the world’s seafood supply by promoting the best environmental choice.” The vision, mission and values are the basis for the MSC’s strategy; all of these elements can be found on the MSC website at www.msc.org. The previous mission statement was one long sentence of around 35 words – it was crucial to refresh it, not simply for reasons of readability, but in order to bind the organisation’s staff and board into a new sense of focus, direction and clarity.

In addition, the MSC began a process of strategic planning at those workshops, where departments would draw up activity plans to support the strategy. This was new territory for several people in the MSC team, many of whom are young, bright achievers who are gaining management responsibilities for the first time. While the initial strategy helped enormously to pull the team together behind a united approach, the MSC had less success in 2001 with the structured action plans and linking those plans to budgets. While the departmental elements of these plans worked fine, the team found it difficult to allocate time and money to inter-departmental activities (which are key to the MSC’s success).

The strategic planning process in early 2002 addressed the shortcomings of the 2001 process. A single “two-day” workshop with follow ups sufficed this time, as the MSC team was happy to reaffirm the 2001 strategic plan and concentrate on measurement and planning for 2002. Although Z/Yen facilitated in 2001 and 2002, the MSC team, gaining confidence, owned the 2002 strategic planning process to a much greater extent than it had owned the 2001 process. For example, rather than Z/Yen going away and writing up the planning documents, MSC managers fulfilled that role. Consultants are valuable when they act as midwives. Expecting them to raise the child is unrealistic and ultimately unproductive. Charities should use consultants when appropriate, but should not see them as a substitute for doing vital work internally.

As an output from 2002, Z/Yen helped the MSC to adopt a more sophisticated budgeting and planning system for time and spend, to help managers to plan their activities, including interdepartmental projects, far more effectively. These management structures will support the MSC’s growth; there were 12 staff when the 2001 strategy was devised, now there are over 20. Further, the action plans contain measurable targets and benefits making it easier to gain project-specific funding where appropriate.

Requisite Viability

Why review the Governance of a 4 year old charity?

Crucial to the MSC is that it must operate openly and transparently. The MSC programme works through a multi-stakeholder partnership approach, taking into account the views of all those seeking to secure a sustainable future. In particular, the MSC constantly needs to "square the circle" between the needs of its commercial stakeholders and its stakeholders in the environmental community. For a charity which will ultimately affect market behaviour, and hundreds of millions of pounds worth of trade in the global seafood industry, good governance is not an option, it is an absolute necessity.

While it might seem strange to have a fundamental review of governance in a charity that was less than five years old and employed fewer than 20 people, it became apparent that the MSC’s initial governance structures were unwieldy, insufficiently open and not transparent enough to facilitate the MSC’s growth.

Thanks to the foresight of the MSC Executive and Trustees (and also thanks to the Packard Foundation who were prepared to fund a governance review), the MSC was able to invest proper attention to this key area.

The process of revising governance

The MSC established an international governance review panel and selected Z/Yen to facilitate the review. Will Martin and Lord Lindsay, both leading experts on environmental matters and quality standards in food, chaired the governance review panel. Will was a Trustee of the MSC whereas Lord Lindsay was brought in as an external expert. In this way the review was both independent whilst overseen at board level.

If the review was to succeed, it was crucial that the multiple stakeholders in the MSC (funders, supporters, staff, food industry, environmental groups, scientists, certifiers and many other interested parties) were all able to participate in the review. The process included innovative use of web-based questionnaires (over 50% of responses were web-based) for ease of use and speed of analysis. It also required an iterative approach; an initial survey was followed up with an outline of the possible new structure for comment and shaping.

As well as facilitating the consultation, Z/Yen ensured that the review followed due process within the UK’s charity law, provided governance models to underpin the consultation and ensured that the lawyers reflected the emerging ideas in the legal drafts.

The emerging governance structure

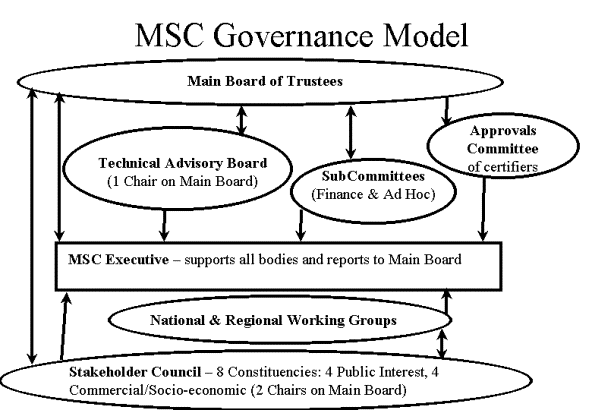

The diagram below illustrates the new structure that emerged from the review.

We found a suitable balance between achieving continuity on the Board of Trustees while ensuring that new blood will regularly join the Board. The Technical Advisory Board and Stakeholder Council replaced an unwieldy trio of Standards Council, Advisory Board and Senior Advisors Group. National and Regional Working groups are informal but influential. Crucially, three members of the board are now elected beyond the board itself, by MSC stakeholders (including critics). This created an important balance between efficiency and openness. The MSC is not open to hijack by one particular sector or interest group, which might paralyse the organization, but the board can no longer simply continue to appoint itself. Another vital new element is that the Stakeholder Council is an evenly balanced body, voting two Co-Chairs to join the full MSC Board.

Implementation of new Governance

The significant changes recommended were approved by the Board in July 2001. The MSC has taken great strides in implementing promptly and effectively the results of this review, including the development of transparent objections procedures. Within a year, the new structures were up and running.

Managing the transition was always going to be challenging, but on the whole it proved a smooth process. The Stakeholder Council, with its franchise based on the various interest groups, was always going to be tricky. The first Stakeholder Council meeting at Methodist Central Hall in Westminster, felt a little as the founding meeting of the UN might have done. (The UN also held its inaugural meeting at Central Hall). We had to work hard at navigating the trust gap between the commercial and environmental interests. Much like the UN experience, once it existed, the stakeholders realized that they were better off with the Stakeholder Council than without it. The second meeting was so much easier. The franchise groupings appointed their representatives and tucked in to the issues at hand.

As the joint chairs of the review put it, “A significant level of consensus has emerged from a range of MSC stakeholder interests. The final recommendations have also incorporated a number of principles for which wide support was evident, including a better defined role and purpose for stakeholders and closer links between stakeholders and the main board”.

Benefits of improved governance

The MSC is a model, award-winning example of best practice in this area. The MSC is transparent in its decision-making; impending issues and decisions continue to be communicated mostly via the world-wide-web, see www.msc.org.

It is not possible to create a perfect governance structure for any organization. But leaving governance to chance, whim, or the views of a handful of vocal interests can be disastrous. The new governance of the MSC is a platform for growth and progress. It provides a suitable balance between stability and flexibility for an organization that is still young and growing. It has generated new interest in the organization, usefully brought critics into the debate and vastly improved organizational effectiveness.

Summary

The three R’s for organizational success are risk control, reward enhancement and requisite viability. The MSC has tackled all three of these areas in the past couple of years. For risk control, it has designed and implemented an appropriate risk management framework. For reward enhancement, it has engaged with staff and trustees to form a consensus on the organisation’s strategic aims and its plans for achieving those aims. For requisite viability, the MSC has consulted widely within its stakeholder base to ensure that its governance has the right mixture of transparency, inclusiveness, stability and flexibility. The MSC is a young charity working in a difficult field. It has achieved a great deal of success in its first few years of life. It’s work on these three R’s should ensure that the MSC can continue to ride the waves towards success.

Brendan May is chief executive of the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC).The MSCenvironmental label now appears on over 125 seafood product lines in 30 supermarkets in 10 countries. The programme’s supporters include HRH The Prince of Wales and the MSC has offices in London, Seattle and Sydney. www.msc.org

Ian Harris is a Director of Z/Yen, the risk/reward management practice, which is currently working with the MSC to help it develop and thrive. Risk/reward management is an innovative approach to improving performance through people, organisation, strategy, systems and intelligence. www.zyen.com.

[A version of this article originally appeared as “The Three Rs”, Charity Finance, Plaza Publishing Limited (March 2003) pages 44-46.]